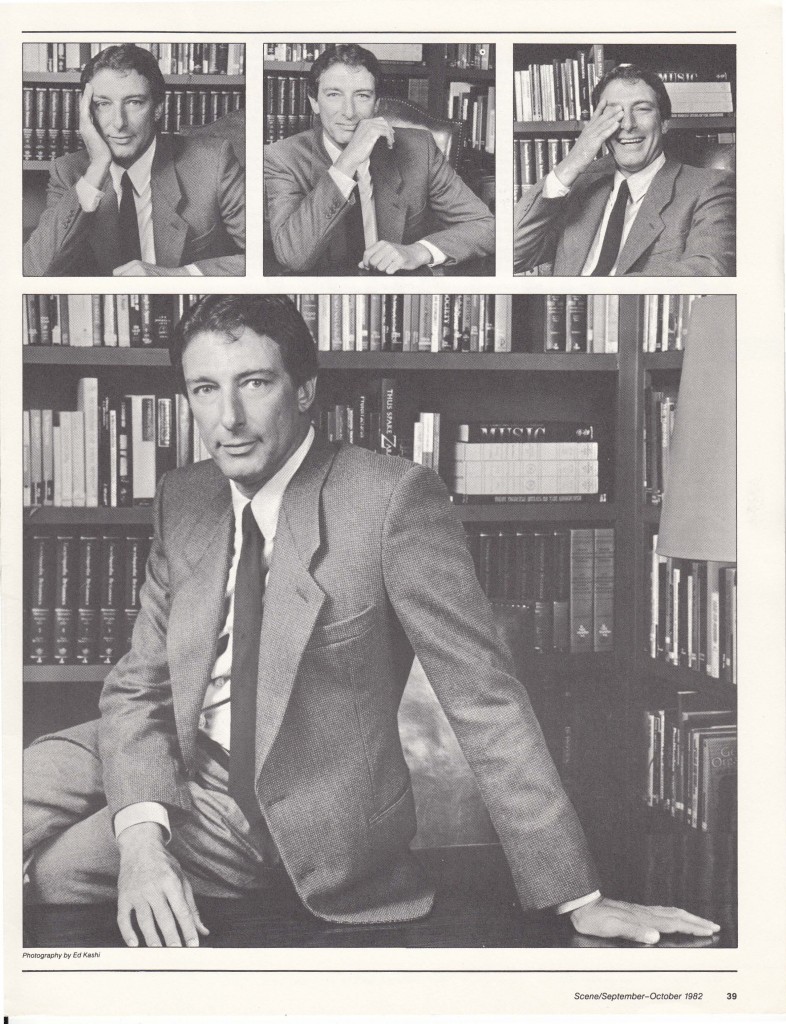

The atmosphere of Werner Erhard’s office in the elegantly restored Victorian on Franklin Street is one of quiet, old-world charm; the decor is massive and comfortable. Like the man, it is powerful and has an air of efficiency.

Erhard is a highly intelligent, communicative man who is intensely charismatic. There is about him a sense of ease, grace and elegance. Basically a shy man who would like to spend his days sailing, he has instead become the center of est, an organization dealing with individual and social transformation. He is to this day highly controversial. Mention his name in public and you will generate responses ranging from pure love and adoration to hate. He has often been accused of being an opportunist. Those who know him say if he is, it stems from a genuine concern about the current state of humanity. They also say he has softened over the years, grown more compassionate and developed a kind of dignity that is inspiring to others.

Born in Philadelphia on September 5, 1935, Werner Erhard was greatly influenced in his youth by the writings of e.e. Cummings. Upon his arrival in California in 1961, Erhard began a self-stylized, multi-disciplined search for inner truth. His own journey led to the founding of the est training. He started out with a small group of people who met regularly with him to explore their interactions and personal growth. That group was to grow to a large organization which would have wide scale social ramifications and Erhard as the leader would become an influential power in a vast network dedicated to actively improving the quality of life. Over the years, both the man and the organization would become strong forces, criticized and lauded with equal fervor.

Now 11 years old, est has changed its name to Werner Erhard and Associates. According to Erhard, the reason behind the name change is that the old organization was constructed as a typical corporate hierarchy. The new organization has been set up as a network to give more autonomy.

Werner Erhard is a man who has made mistakes, including deserting a wife and four children. But he believes he has made peace with his past and the people in his past who were hurt by his actions. In fact, Werner Erhard and Associates has become a family affair. Erhard’s sister Joan and brother Harry both work on the staff. Another brother, Nathan, is a consultant, and former wife Pat Campbell is also on staff. In addition to the four children from his first marriage: Clare, 28; Lynn, 27; Jack, 23: and Deborah, 22, Erhard has had three more children with his wife of 20 years, Ellen: Celeste, 19; Adair, 17; and St. John, 14.

Erhard is a San Franciscan. He lives and works in this city and he loves it. (Because of Erhard’s love for the sea, he and Ellen recently sold their Marin County home and now live aboard a large boat.) He actively supports San Francisco socially, politically, artistically and financially He is a great benefactor of the arts and regularly attends the opera, the symphony and special events. Erhard believes that culture is the element that gives a city its excitement and aliveness.

Brilliant at sensing societal shifts, Werner Erhard has increasingly turned toward community issues. The organization has been conducting Community Workshops, which include projects such as work with battered women, runaway children and a project called Youth at Risk—a 10-day training for juvenile delinquents.

Recently, I talked with Erhard about his philosophy and commitment to community.

Is there anything that you find idiosyncratic about the San Francisco community?

The Bay Area is in my view one of the best places in the world to live. No question about it. I contrast it with Minneapolis, which is one of the best cities in the world. When I compare San Francisco to Minneapolis, our city should be far, far ahead in terms of a great place to live, but Minneapolis outdoes us. Minneapolis is a city in which one is inspired by the quality of commitment the citizens have for their city. Theirs is a very rich, well-planned cultural life. The corporate community is commit-ted to the city and that commitment has provided a wide base of citizen support and participation. It is a remarkable place with wonderful people. And then there’s San Francisco—beautifully endowed with an incredible kind of natural resource, plus the architecture and the tradition. We have some outstanding people in this city—people who have devoted their lives to making this city the best possible place to live. But somehow we have not reached that kind of citizen commitment and support with a sense of what can and needs to be done here. And so for the most part, the wellbeing of the city is left in the hands of a relatively small group of people who are working tirelessly and courageously, but without the commitment of a significant base of citizens and without a sufficient commitment from the corporate and academic communities. Their support could make a real difference, and San Francisco could fulfill its incredible promise.

What do you think causes this lack of commitment?

I think it is a lack of a certain awareness—awareness of the difference between what is predictable and what can be brought forth. If your city arises out of a vision, it most certainly will reflect to some degree the circumstances out of which it arises, but it will also begin to reflect that vision.

What I think we lack in the Bay Area is a sense that vision can make a difference. People often feel that the wonderful capacities for vision some people have is impractical. They are called starry eyed dreamers. But we now live in an era where people of vision are the only practical people. Functioning at the level of what is reasonable is as impractical as one can get. A look at the future is not only dim, but perhaps bleak, therefore it is impractical to be merely reasonable. If we are to be truly practical, we must bring forth a vision enabling people to see possibilities beyond the apparent circumstances. And in my view, what would enable San Francisco to experience a breakthrough is for citizens to recognize that distinction and to be willing to bring forth a vision—not in ignorance of the circumstances or what is reasonable, but in addition to at/ that.

Are there certain principles that would allow this to occur, not only in San Francisco, but in society in general? When we talk about human nature, one of the things we are talking about is a particular kind of human nature in a particular condition. We have accepted the condition that people’s lives don’t make much difference. If the condition in which you and I are human were altered, what is possible in the scope of human nature would be altered. Life never needs to turn out predictably. Human beings have the capacity to intervene in the orderly unfolding of circumstances, to produce an outcome which is basically unpredictable given those circumstances. Thus the condition is actually self-imposed. Most of us don’t know that. We think that the conditions in which we live are a function of society our physical environment, our family, or how we grew up. The work we have done in the last 11 years has demonstrated conclusively that it is possible for human beings to alter the conditions. To do so, for oneself, and to do so as a contribution to society and the environment where one lives, is one of the principles underlying a breakthrough for community

You really have a passion for community. Why is that?

First of all, community is a fundamental self-expression. It’s part of what happens to human beings naturally—like family. It is a place where individuals can truly make a difference and where people can know that they can operate beyond predictability.

You have something called The Community Workshop. What are you exploring in it?

We’ve actually done two workshops with a total of about 1600 people here in the Bay Area. We are developing a prototype that will be used in our centers throughout the world to support people in bung able to be effective in their community, rather than simply having a list of complaints and gripes and feeling like there is nothing they can do. A lot of the work is allowing people to get in touch with the fact that they have the power to bring forth in themselves those qualities which will actually make a difference in their community, their family and their work.

How do you approach problem solving in a community?

One of the things that I have learned is that it’s very difficult to get to the actual causes of the problems in a community And let me say parenthetically, I’m making a distinction here between the explanation we give for things and the actual causes of them. At any rate, it is difficult to get to the actual causes when they are obscured by a simple lack of integrity by the people “in community.”

What do you mean, lack of integrity?

We discovered that when people don’t stand behind their word, things stop working. And you can’t even discover why they stop working because the source is obscured by a basic lack of integrity. Here’s how I think it works: You go to the doctor and the doctor comes up with a tentative diagnosis that you have disease X. He tells you to take these pills three times a day. Most of the time you remember twice a day, sometimes only once a day and occasionally not at all. You go back to the doctor with the same complaints. The doctor now rules out disease X because he knows that he gave you the pills and he thinks you took them. He now has to conclude that you have disease Y and he gives you medication for that which, of course, doesn’t work. It just keeps getting more and more en-mired. The same thing holds true for community.

What does that mean to the individual?

The people in the community start to have the sense that they are really only going through the motions, that they can’t really make any difference; and then their choices become insignificant. There are all those little choices we all have to make every day like whether to be concerned about the interests of our neighborhood, whether to walk over the trash in the street or pick it up.

Earlier you mentioned basic integrity. Is there another kind?

There is a kind of middle level where it means to be true to one’s ideals. It’s a matter, for instance, of supporting those things which you have said you are interested in. And it’s a matter not of pride about one’s honesty, but responsibility about one’s integrity. You really can’t discover the source of the problems when you are being untrue to your own ideals. It sounds like a very personal matter—if I am not true to my ideals, too bad for me. But the truth is it’s too bad for the community as well.

Can you give me an example?

We’ve been very goal oriented in this society. A society which lives by motives alone looks like the society we’ve got. And unfortunately, we have even lost our productive edge in this country, and in my view a lot of that reflects the fact that people in business don’t have any sense that who they are in that business makes any difference. I just came back from doing some organizational consulting with one bf the major corporations in the space program. And it is very interesting to talk to these people because they remember the great days of the space program—to the time we put the first man on the moon. They really know what it is like to work in an environment in which each little choice you make and the kind of person you are really makes a difference. They want that back in their industry. And to some degree they think that what determines whether one makes a difference is the objective one is working on. It isn’t the objective, it is a quality which people can bring forth in themselves when they are aware of the possibilities in themselves.

Is your workshop primarily educational, or are the people in the workshop actively involved in community projects?

There have been about 80 separate projects ranging from working with 10 juveniles or “youths at risk” as we like to call them, to gangs in the barrios of East Oakland. The 10 youngsters were supported in getting jobs and keeping their jobs, so that they could develop the skills that one needs to survive in society. Hopefully, they will go beyond mere surviving in this society to actually becoming contributing members.

What do you mean when you say, “People don’t know they make a difference?”

I mean literally that people think the choices they make in life don’t make any difference. They feel as if the decisions they make don’t matter much. In fact, we live in a kind of unseen agreement that nobody really makes any difference. When you do make a difference you are empowered. People are often unwilling to be empowered.

Why would people be unwilling to be empowered?

If you are empowered, you suddenly have a lot of work to do because you have the power to do it. If you are unempowered, you are less dominated by the opportunities in front of you. In other words, you have an excuse to not do the work. You have a way out. You have the security of being able to do what you have always done and get away. If you are empowered, suddenly you must step out, innovate and create. The cost, however, of being unempowered is people’s self-expression. They always have the feeling that they have something in them that they never really gave, never really expressed. By simply revealing the payoffs and costs of being unempowered, people have a choice. They can begin to see that it is possible to make the choice to be empowered rather than to function without awareness. Empowerment requires a breakthrough and in part that breakthrough is a kind of shift from looking for a leader to a sense of personal responsibility The problems we now have in communities and societies are going to be resolved only when we are brought together by a common sense that each of us is visionary. Each of us must come to the realization that we can function and live at the level of vision rather than following some great leader’s vision. Instead of looking for a great leader, we are in an era where each of us needs to find the great leader in ourselves.

by Loretta Ferrier

Scene/September-October 1982